3) What constitutes an actionable nuisance (scope)?

This is the third in a short series of posts considering the consequences of the judgment of Leggatt JSC in Fearn v. Tate Gallery Trustees [2023] UKSC 4 [2023] 1 WLR 339, in which he listed what he described as a set of applicable principles relevant to the assessment of private nuisance.

In post (1) I examined the brick kiln (and other) cases which preceded Walter v. Selfe (1851) in order to try to discover whether the contemporary notion of the “threshold” test is lower than the test which was applied when it was first established. The authorities show that there has been no such ‘deflationary’ effect over the years. In post (2) I looked at the question whether or not the “threshold” test is truly objective, or whether it adapts to individual tolerances. (It does).

The Courts have recognised that the “threshold” test must essentially be an objective one because its scope covers the amenity value of land and interests in land. This post summarises Leggatt JSC’s conclusions as to scope because (i) they are crucial to any understanding of what constitutes a nuisance, and (ii) they led the Supreme Court specifically to decide that the lack of privacy occasioned to the occupants of the flats affected by the Tate’s viewing platform amounted to a private nuisance.

Leggatt JSC made a reference to a seminal article by Professor Newark, who described private nuisance as a tort to land, by which he meant that its subject matter is wrongful interference with the claimant’s enjoyment of rights over land: “The term ‘nuisance’ is properly applied only to such actionable user of land as interferes with the enjoyment by the plaintiff of rights in land” (para.9 of the judgment).

The JSC continued: “It follows from the nature of the tort of private nuisance that the harm from which the law protects a claimant is diminution in the utility and amenity value of the claimant’s land, and not personal discomfort to the persons who are occupying it, making a further quotation from Professor Newark: “the interest of the plaintiff which is invaded is not the interest of bodily security but the interest of liberty to exercise rights over land in the amplest manner. A sulphurous chimney in a residential area is not a nuisance because it makes householders cough and splutter but because it prevents them taking their ease in their gardens” (para.11).

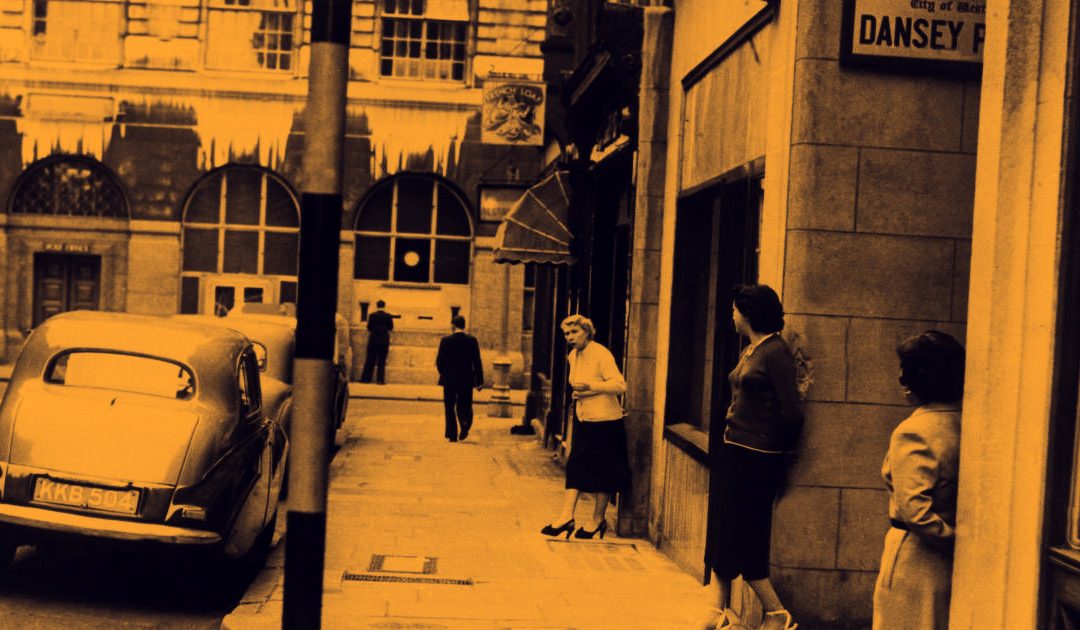

As to what constitute a nuisance affecting land, Leggatt JSC saw no boundaries to the scope of the tort. Whilst it will generally constitute something emanating from land, and it may also cause physical damage (a distinct type of nuisance not considered in Fearn), that is by no means always the case. The effect of smoke, noise and vibrations are examples of the type of ‘intangible’ nuisances covered by the principles discussed in Fearn. Leggatt JSC looked at more remote objects of the tort, including the dazzling glare from the deflection of the sun’s rays in Greenwood (1984), the sight of prostitutes in Thompson-Schwab (1956) or the sex shop in Laws. There was no reason not to extend private nuisance to persistent intrusion by looking.

Some of the judge’s conclusions, however, are controversial. Thompson-Schwab, for instance, allowed the Court in that case only tentatively to grant an interim injunction, pending final resolution at another date. So too, there is a degree of controversy as to whether a finding in nuisance excludes a finding of trespass (see para.12 of Fearn). In the U.S. it has been recognised for many years that some escaping items which cause pollution constitute both a nuisance and a trespass. In Southport Corporation (1954-6), the question whether or not oil which escapes from a ship at sea can constitute a nuisance, was never satisfactorily resolved between the trial judge, Court of Appeal and House of Lords.

That all said, there are certainly continuing developments as to what constitutes a nuisance in the early twenty-first century, the connection between the scope of nuisance and the enjoyment of land being an area of uncertainty. Private nuisance has been described as “protean” after the Greek god Proteus who constantly changed his shape. Interference with radio waves is a nuisance (Network Rail Infrastructure (2004)), but so far, lighting has only been recognised as a nuisance in statutory nuisance provisions, and not at common law. No doubt this is an area which will give rise to future actions in which some of these uncertainties will be examined in the light of Fearn.

Gordon Wignall

23 May 2023

Principles of Private Nuisance as set out in Fearn:

- What constitutes an actionable nuisance (scope)?

This is the third in a short series of posts considering the consequences of the judgment of Leggatt JSC in Fearn v. Tate Gallery Trustees [2023] UKSC 4 [2023] 1 WLR 339, in which he listed what he described as a set of applicable principles relevant to the assessment of private nuisance.

In post (1) I examined the brick kiln (and other) cases which preceded Walter v. Selfe (1851) in order to try to discover whether the contemporary notion of the “threshold” test is lower than the test which was applied when it was first established. The authorities show that there has been no such ‘deflationary’ effect over the years. In post (2) I looked at the question whether or not the “threshold” test is truly objective, or whether it adapts to individual tolerances. (It does).

The Courts have recognised that the “threshold” test must essentially be an objective one because its scope covers the amenity value of land and interests in land. This post summarises Leggatt JSC’s conclusions as to scope because (i) they are crucial to any understanding of what constitutes a nuisance, and (ii) they led the Supreme Court specifically to decide that the lack of privacy occasioned to the occupants of the flats affected by the Tate’s viewing platform amounted to a private nuisance.

Leggatt JSC made a reference to a seminal article by Professor Newark, who described private nuisance as a tort to land, by which he meant that its subject matter is wrongful interference with the claimant’s enjoyment of rights over land: “The term ‘nuisance’ is properly applied only to such actionable user of land as interferes with the enjoyment by the plaintiff of rights in land” (para.9 of the judgment).

The JSC continued: “It follows from the nature of the tort of private nuisance that the harm from which the law protects a claimant is diminution in the utility and amenity value of the claimant’s land, and not personal discomfort to the persons who are occupying it, making a further quotation from Professor Newark: “the interest of the plaintiff which is invaded is not the interest of bodily security but the interest of liberty to exercise rights over land in the amplest manner. A sulphurous chimney in a residential area is not a nuisance because it makes householders cough and splutter but because it prevents them taking their ease in their gardens” (para.11).

As to what constitute a nuisance affecting land, Leggatt JSC saw no boundaries to the scope of the tort. Whilst it will generally constitute something emanating from land, and it may also cause physical damage (a distinct type of nuisance not considered in Fearn), that is by no means always the case. The effect of smoke, noise and vibrations are examples of the type of ‘intangible’ nuisances covered by the principles discussed in Fearn. Leggatt JSC looked at more remote objects of the tort, including the dazzling glare from the deflection of the sun’s rays in Greenwood (1984), the sight of prostitutes in Thompson-Schwab (1956) or the sex shop in Laws. There was no reason not to extend private nuisance to persistent intrusion by looking.

Some of the judge’s conclusions, however, are controversial. Thompson-Schwab, for instance, allowed the Court in that case only tentatively to grant an interim injunction, pending final resolution at another date. So too, there is a degree of controversy as to whether a finding in nuisance excludes a finding of trespass (see para.12 of Fearn). In the U.S. it has been recognised for many years that some escaping items which cause pollution constitute both a nuisance and a trespass. In Southport Corporation (1954-6), the question whether or not oil which escapes from a ship at sea can constitute a nuisance, was never satisfactorily resolved between the trial judge, Court of Appeal and House of Lords.

That all said, there are certainly continuing developments as to what constitutes a nuisance in the early twenty-first century, the connection between the scope of nuisance and the enjoyment of land being an area of uncertainty. Private nuisance has been described as “protean” after the Greek god Proteus who constantly changed his shape. Interference with radio waves is a nuisance (Network Rail Infrastructure (2004)), but so far, lighting has only been recognised as a nuisance in statutory nuisance provisions, and not at common law. No doubt this is an area which will give rise to future actions in which some of these uncertainties will be examined in the light of Fearn.

Gordon Wignall

23 May 2023